Every fox hunt must begin with scouting for fox poop and fox tracks.

Find fox poop and fox tracks before you fox hunt!

Successful fox hunter know, “You have to be where the foxes are, to call them in.” Scouting means finding a suitable habitat, then discovering undeniable proof they currently inhabit that land.

Foxes can live anywhere, but they prefer open fields and meadows overflowing with rabbits, insects, and fruits. Once you find a place that meets that description, it’s time to scout it out.

Fresh fox poop and tracks are best!

What you will be looking for is fresh sign (scat and tracks). What you will need to be able to do is tell fox scat (poop) and tracks (paw prints) from those of other animals and determine the freshness (age) of that sign.

Fox tracks.

Fox paw prints are approximately 1.75 to 2.5 inches long by 1.5 to 2″ wide.

How to tell fox tracks from domestic dogs prints.

New fox hunters often find a set of prints and find themselves wondering if a dog or a fox made them.

Thankfully, there is one surefire way to tell if a track was made by a dog or by a fox or coyote: Can you draw an X between the negative spaces?

Here’s what I mean:

Full disclosure: I stole this incredible tip from the wizards at: https://www.wildernesscollege.com/fox-tracks.html. They also pointed out that gray fox can retract their claws, therefore leaving no claw prints at times.

Now, notice how you cannot make the same mark on a dog print without touching the heel mark?

Aging fox tracks.

When it comes to aging those fox tracks you found, the weather in the days leading to your discovery is critical. While mud holds tracks the longest, snow is a frequent weather event during most regular fox hunting seasons and often provides the best track aging information.

There are two degrees of freshness for fox hunters when using aging tracks: Tracks more than a day old and 0-3 hours old tracks.

Tracks older than one day provide you with proof that a fox inhabits the land. For most hunters, this is enough to scout out the area for an excellent calling stand location and return later to hunt the spot.

0-3 hour old tracks mean anything from perhaps still within calling range to you spooked them coming in (check the sign for galloping gait evidence).

Aging fox tracks in the snow.

It’s all about the recent weather. Tracks in snow start off sharp and clean. As the temperatures rise, those sharp edges round off. Finally, as temperatures dip below freezing, ice crystals develop inside the track.

Tracks in deep snow are harder to age than those in light snow. With deep snow, you’ll have to examine the kicked-out (excavated) snow to determine its age. Excavated snow is exposed to the elements, especially melting.

You know they were made after the last snowfall if good clear tracks in the snow have no snow in them.

Has any snow built up inside the track if the wind is blowing hard enough to move the snow on the ground?

If you find the track has an icy surface in the morning, then the print froze at some point overnight.

If you find clean, fresh tracks in the morning, check for ice crystals. No ice crystals mean it’s from that morning.

If you find a fresh sharp track when the temps are above freezing or the sun is shining, and the sky is clear, that track is new and hot. 0-3 hours.

Be sure to check out my red and gray fox hunting book!

Aging fox tracks in the mud.

With mud, knowledge of recent weather still plays a critical role, but now we can add gravity to the list of things that aid you to track.

If a fox fled minutes before you arrived and left tracks in the mud, here’s what you’ll find.

Along the outside of the print, there will be fissured walls and bits of soil. Gravity will soon pull these materials down into the track. If none have yet to fall, the print is exceptionally fresh.

As that track ages, the first changes occur in the color of the cracks and fragments displaced by the fox’s paws. These slivers and the edges of the track will dry out faster than the print itself.

As time progresses, the track’s sharpness will dull, and its edges will round as gravity takes hold.

Eventually, debris will fall into the print, the rain will collect in it, and heavier rain will wash it away. Knowing what day it rained or when the wind would have been blowing strong enough to move debris into it will help you determine the track’s age.

Aging fox tracks in the sand.

The freshest tracks in the sand will have raised surfaces near the crests of their walls that have not yet had time to begin to dry out. If you find a track in this condition on windy or sunny days, it’s 0-3 hours old.

A track found in the early morning that has no dew in it is from that morning. If it has dew in it, it’s from some point before sunrise.

If the track appears fresh and dry, but it recently rained, it’s from after the rain ceased.

Fox tracks tell you what the fox was up to.

A fox has four speed settings while traveling; walking, trotting, loping, and galloping. Each speed leaves a different track, and each one tells you something about the behavior and goals of the fox that left them.

The most relaxed gait (the pace or manner of walking) of a fox is called “the walking gait.” The walking gait typically results in only one foot every being off the ground at any one time. When walking, the fox’s legs move forward in an alternating, diagonal string of right front leg followed by the left hind leg, the left front leg, and the right back leg.

A walking fox is calm but constantly examining the area around itself. Foxes walk around dens, when in areas providing good visibility and long-range scents, when accompanied by other group members, and when they are well fed and not engaged in hunting.

Fox tracks made while walking.

Direct Register Walk: Anytime the hind paw steps into the space just occupied by the front paw on the same side; this is called a direct register. The direct register walk is seen chiefly in “safe” areas (places well known to the predator), presenting other topographical problems. It permits the surest of footing and prevents tripping into holes or over other obstructions.

There are two unique walking gaits.

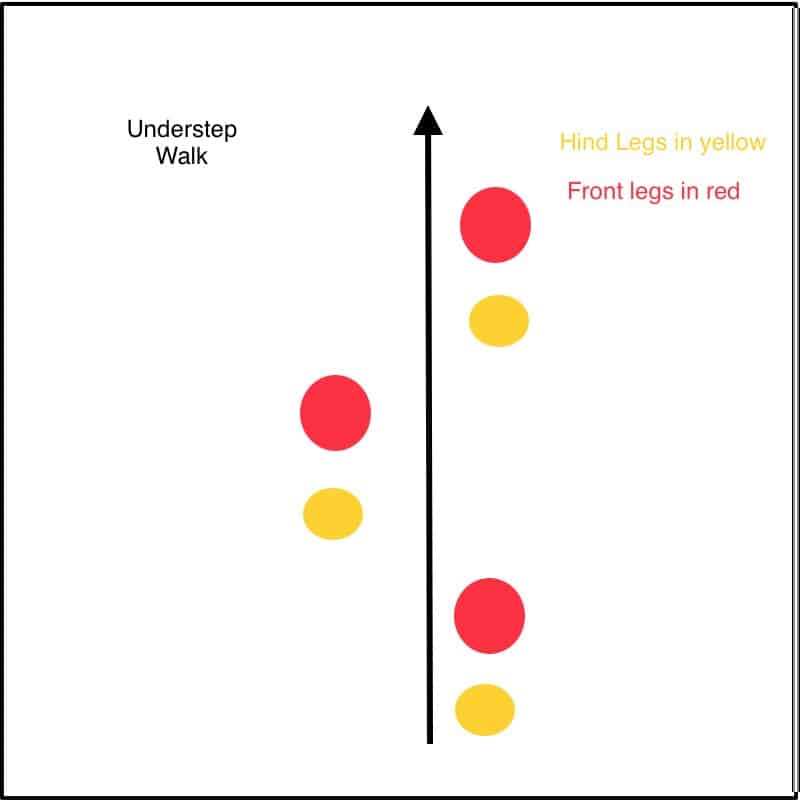

- Understep Walk: The understep walk is when the hind paw lands behind the front foot on the same side. You’ll find the Understep Walk used where male foxes have changed guard/bedding positions near occupied dens. While it often suggests a level of great comfort on the part of all predators, where foxes have had to slink away unseen from a potential threat, they will use this gait.

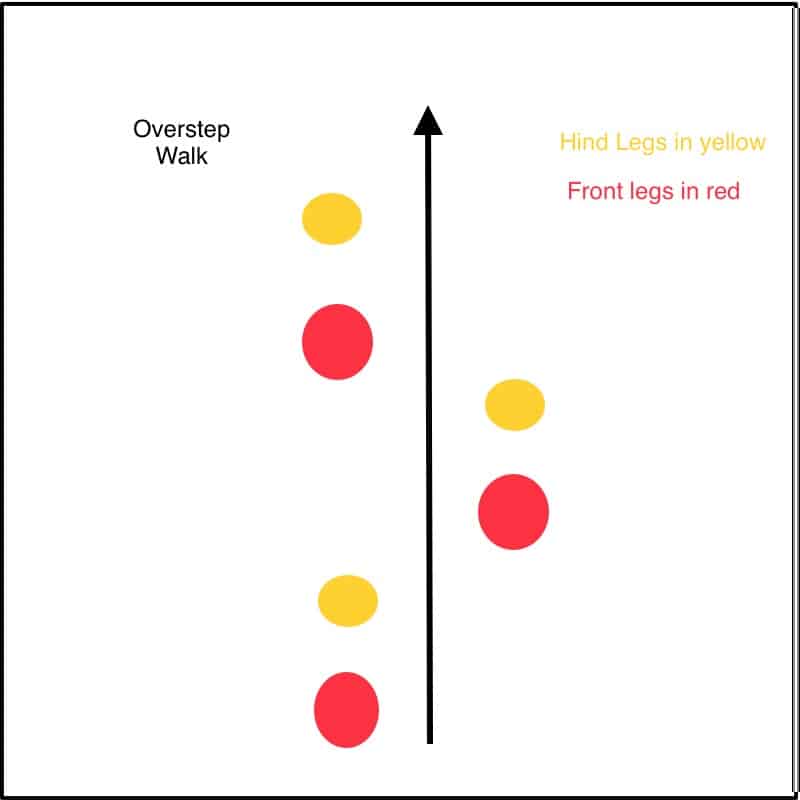

2. Overstep walk: The most common walking gait of a predator. A trotting predator may switch to the Overstep Walk when something catches its attention (a scent on the ground that needs to be examined, etc.).

Two special notes:

- If you are tracking a wounded fox, suddenly switching to a walking gait is a good sign the fox is fatiguing. Related: How to Track a Wounded Coyote

- When you find any sign of an unwounded, walking fox, that animal is a resident inside their territory.

Fox tracks made while trotting.

Trotting is faster than walking, but it requires little effort, covers more ground in a shorter time, and is maintainable for long stretches at a time. When trotting, the legs move forward in diagonal, alternating pairs, which typically results in two feet being off the ground at any one time. As a result, foxes spend more time trotting than in any other gait.

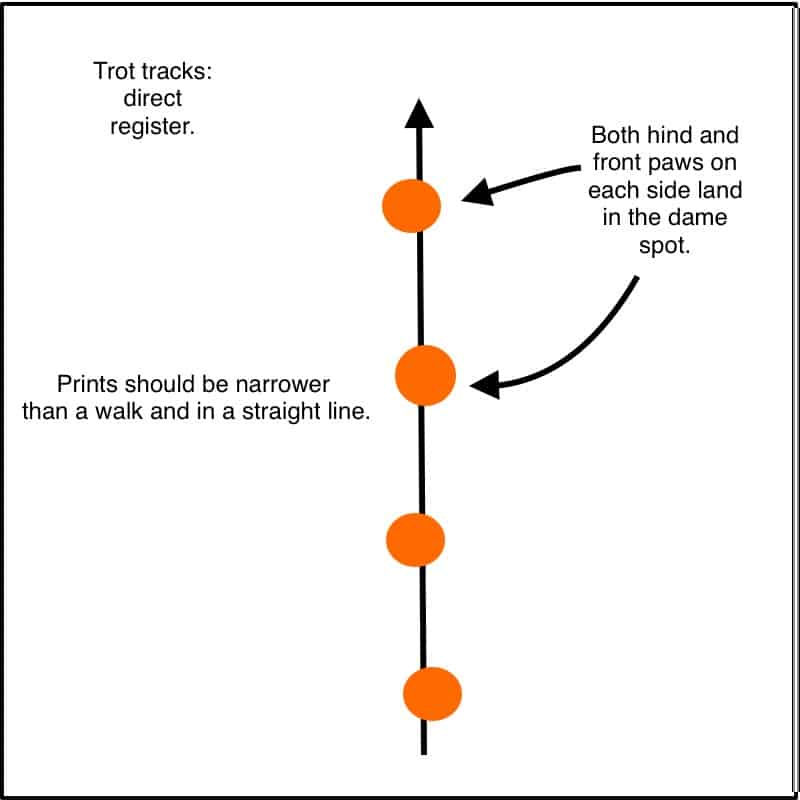

Trotting foxes leave tracks that are very narrow and straight.

Direct register trot: When a fox is patrolling or hunting inside its territory, the direct register trot is its usual gait. The understep and overstep trots are rarely seen outside of some form of group interactions.

Fox tracks made when moving with speed.

Loping: Loping is the first stage of running. A loping fox typically has only one foot on the ground at any one time. Loping is almost always a sign that the animal is in some level of concern.

While hunting, loping will be used where smaller prey hides in taller grasses and low thick brush.

Galloping: Foxes gallop for two reasons, to escape and to pursue prey. An escape using a gallop will be a straight line. Twists and turns will mark a pursuit using a gallop as the fox reacts to its prey’s attempts to flee.

When galloping, all four feet can be off the ground at the same time.

Fox poop.

Scat, feces, poop, or whatever you wish to call it, is like snowflakes; no two are alike. Therefore, trying to determine who dumped (sorry) what on the ground can be difficult. The location, a few essential characteristics, and, if you are lucky, some tracks nearby should help you identify the animal, but there is often an element of uncertainty.

Fox poop size, shape, and color.

Fox poop averages two inches in length and a ½ inch in diameter. Often loaded with hair, undigested insect parts, and seeds from berries and fruits. Fox scat is pointed at both ends and has an unusual odor. I’d call it putrid.

Start every fox hunt by scouting for fox tracks and fox poop.

Using fox scat and paw prints to find where the fox live and hunt may be the missing tool in your predator hunter’s kit.

Hopefully, this article will help you find the perfect calling locations, so that every hunt ends with a track that looks like this one.